With the invention of the telephone came instant communication. Not ticks and dashes translated into letters, but simply using your voice. I imagine that at first people felt strange talking into a machine and then expecting a reply. Now, we don’t think twice about it, but during Alexander Graham Bell’s time it was borderline insanity.

With the invention of the telephone came instant communication. Not ticks and dashes translated into letters, but simply using your voice. I imagine that at first people felt strange talking into a machine and then expecting a reply. Now, we don’t think twice about it, but during Alexander Graham Bell’s time it was borderline insanity.

In April of 1871, Bell moved to America. He had accepted a teaching position at the Boston School for the Deaf. Within just days, Aleck made a huge impact on the school. Using the knowledge his father had passed down to him, he was a very successful teacher. Next, he began tutoring Deaf children. This gave him more time to focus on his inventions. At the time, he was working on something he called the harmonic telegraph. It was the idea that if you used varying tones, you could send multiple messages along the same wire.

Think about the idea for just a moment, and pretend that you’ve never used or heard of a telephone before. Now think of the concept, talking through a wire. Does that sound a little crazy to you? It did to most people. It took a special kind of bravery to pursue such an extraordinary idea. Even after he proved that the invention worked, people thought it would never become common, that it was just a toy. So he proved them wrong again.

Tele means distance, or from afar. Phon means sound. Put them together, and telephone means sound from afar.

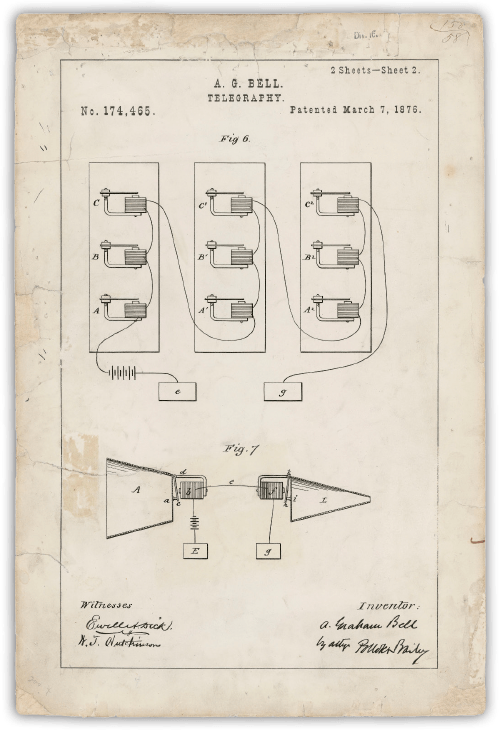

His idea for the telephone was possible. Experiments soon began. Alexander Graham Bell’s mind was constantly turning. He moved fast, and thought even faster. Exploring his ideas, he devoted himself to his inventions, sacrificing everything, at times, even food. He and Watson lived together in a low-rent attic. What little money they had went to supplies. Often, Mr. Watson would be wakened in the middle of the night by an excited Bell who couldn’t wait until morning to try out a new theory. It was after many attempts and much work that the first phrase was spoken clearly through the telephone on March 10th, 1876. A frantic Bell said, “Mr. Watson, come here, I want you.” Calling to his friend, Aleck had just spilled acid on himself. Watson came running breathlessly in and told Bell that he had heard his words as clearly as if he were standing in the room. After that, Aleck cared little about the burning acid.

It would take a little time, and a lot more work before the telephone became acceptable to the public. Bell and Watson travelled to various cities making demonstrations of their invention. People began to see what the future could be. They thought of how much less complicated it would be to communicate with a friend, or call on the doctor. They felt safer knowing that it would only take a phone call for the fire department to dispatch help. Four years after the first phone call, over sixty thousand phones had been installed in America.

On January 25th of 1915, Alexander Graham Bell and Thomas Watson made history once again. A network of telephone lines had finally been built from one end of the country to the other. Using the familiar instrument before him, Aleck spoke from New York to his faithful assistant who was more than 3,000 miles away. With a clever wit, and a feeling of nostalgia, Bell used the same fateful words that had changed his life thirty-nine years before, “Mr. Watson, come here, I want you.” Watson’s reply: “It will take me five days to get there now!”

To download activity pages for this profile that include a word search, crossword, map and writing assignment, click here.

shley Wiggers grew up in the early days of the homeschooling movement. She was taught by her late mother, Debbie Strayer, who was an educator, speaker, and the author of numerous homeschooling materials. It was through Debbie’s encouragement and love that Ashley learned the value of being homeschooled. Currently, Ashley is the co-executive editor of Homeschooling Today magazine, public relations director for Geography Matters, and the author of the Profiles from History series. Ashley makes her home in Somerset, KY, with her loving husband, Alex, and their precious sons, Lincoln and Jackson.